Visiting Velo-Orange

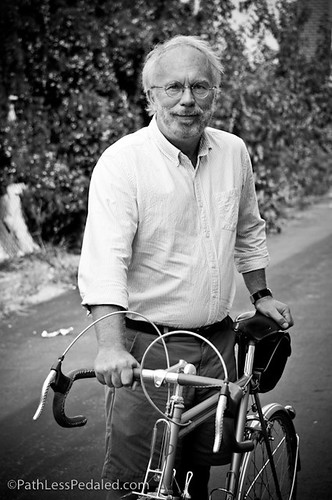

Chris Kulczycki was trying to decide what to name the new company that he was about to start. “The orange bicycle. The orange bike?” Not quite satisifed and thinking it should sound a bit more French, Chris settled on “Velo-Orange.” The orange bike in question is an orange Ebisu that now hangs on a wall in the corner of their nondescript warehouse building in Annapolis, Maryland. “It’s as fine a bike as I’ve ever ridden.”

Velo-Orange began by reselling a lot of NOS (“new old stock”) parts (Simplex derailleurs, shifters, etc.) that Chris found through relationships with Mel Pinto and some European companies that had boxes of things that supposedly no one wanted anymore. After the success of selling the NOS parts, they found that there was a market for the sort of vintage parts that he was interested in.

The first part they produced was a bicycle bell brazed to a headset spacer. Since then, they have since ventured into components (racks, handlebars, stems, pedals, saddles, cranks), soft goods (handlebar bags, panniers, seat bags) and even frames. To this day, there is still a little element of surprise when they produce a product and it sells out. Take for example the wheel-stabilizer, an obscure part by American standards, which has been a strangely robust seller.

When we visited Velo-Orange, it was a relatively slow day. The showroom was a little more bare than usual, a lot of items had been packed up for InterBike. There was no large order arriving and the explosion of activity that usually ensues. The only real big appointment was a haircut that Chris was going to get before InterBike. Maybe two or three people came by the showroom to buy things directly, otherwise a majority of the business occurs online or with their dealers around the country.

Tom and Perry gave us a tour of the facilities. There was the shipping department, where folks were boxing orders. They had a small photo studio in one of the warehouse spaces with a DIY cardboard softbox where they photographed products for the website. There was also a plastic bin of prototype parts that didn’t quite make the cut – hubs and cranks and handlebars that weren’t going to see the light of production.

We talked to Tom about being compared with Rivendell. “People always want to put Rivendell and Velo-Orange in a cage and wait for a cock fight,” but he sees their relationship as more of a “cooperative one.” They share a similar market that has been ignored by the larger bike companies – “people who ride but don’t race.”

In the last few years, Velo-Orange has been, by all accounts, an undeniable success, growing 40% every year. Their operations have moved a few times to accommodate their growth and Chris has had to hire more staff to keep up with shipping orders. Their success hasn’t gone unnoticed by larger bike manufacturers that have tried to emulate the “VO style.” There has been a slurry of city bikes with swept-back handlebars, inverse brake levers and porteur racks.

Tom readily admits that they aren’t making new products, but are refining old designs with new processes and materials. And yet, there is a bit of resigned frustration when a large company introduces a new bike that so closely mimics the bicycles that Velo-Orange is known for. It is a story of the tail wagging the dog, of a relatively small company taking the risks in the market to reproduce parts that most people had forgotten about and in the process influencing larger bike companies.

In the end, the trend is good for those that “ride but don’t race,” the silent majority in the middle that larger companies have abandoned for the extremes. Chris and the Velo-Orange crew probably view themselves more as a business than a bike advocacy group. But by remaking components that excite people to ride every day (not just race day), they are inadvertently helping bikes move to the mainstream where they need to be.

Tags In

5 Comments

Leave a Reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

Subscribe

Patreon

Join Team Supple on Patreon

PayPal

Thanks for this profile. I’ve been a happy customer of VO for a couple years because they make stuff I find both useful and beautiful. The only frustration has been products that are temporarily unavailable because they’re a small operation and need to wait for production runs. I hope their continued growth means that they’ll have more of their fine products available all the time.

I also appreciate that Chris doesn’t pull punches about the skills required to use some of their products. I installed a set of original randonneur racks, and I was grateful for the tips about taking time to carefully measure and to get a new carbide-tipped drill bit to drill holes in the tang.

And Russ and Laura: If you find yourselves in western Massachusetts (Hadley, between Amherst and Northampton) between now and late May 2011, let me know; our guest room may be available.

Awesome backstage tour and history of Velo-Orange! I really enjoyed this post. 🙂 Fantastic portraits Russ. Its wonderful to see the world of vehicular-cycling shrink a bit by meeting these folks through the eyes of you and Laura.

Great post! I love Velo-Orange and what they do for cycling!

I’ve ordered several items from Velo Orange over the past year or two and have never been disappointed with the service. Hoping to replace my aluminum and carbon day-tourer with their beautiful Rando frame soon. I like that they offer frames in a build kit, something other bike companies should consider.

Thanks for the peek inside this unique company,

Jack

VO has some great stuff!!!!!